EU & China Holding Talks On Electric Car Tariffs Ahead Of November Deadline

China and the European Union have agreed to start talks on the planned imposition of tariffs on electric vehicles made in China and imported into the European market, senior officials of both sides said on June 22, 2024. According to CNBC, German economy minister Robert Habeck said he was informed by EU commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis that there would be concrete negotiations on tariffs with China. The Chinese commerce ministry said it had agreed to start consultations regarding the EU’s anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs.

“This is new and surprising in that it has not been possible to enter into a concrete negotiation timetable in the last few weeks,” Habeck said in Shanghai, calling it a first step with many more necessary. “We are far from the end, but at least, it is a first step that was not possible before. What I suggested to my Chinese partners today is that the doors are open for discussions and I hope that this message was heard,” he said in Shanghai after meetings with Chinese officials in Beijing.

Habeck’s visit was the first by a senior European official since Brussels proposed hefty tariffs on imports of Chinese made EVs to combat what the EU considers excessive subsidies. He said there is time for a dialogue between the EU and China on tariff issues before the duties come into full effect in November and that he believes in open markets but that markets require a level playing field. Proven subsidies that are intended to increase the export advantages of companies can’t be accepted, Habeck said.

How Big Are Chinese Subsidies?

We have heard a lot about China subsidies, but much of it has been fairly general, broad brush statements — until now. On June 20, 2024, the Center for Strategic and International Studies said it had the numbers to back up that speculation.

From 2009 to 2023, we calculate that Chinese government support cumulatively totaled $230.8 billion. Absolute funding annually was around $6.74 billion in the first 9 years of our analysis (2009-2017), as the sector was just getting off the ground. Spending roughly tripled during 2018-2020, and then has risen again sharply since 2021.

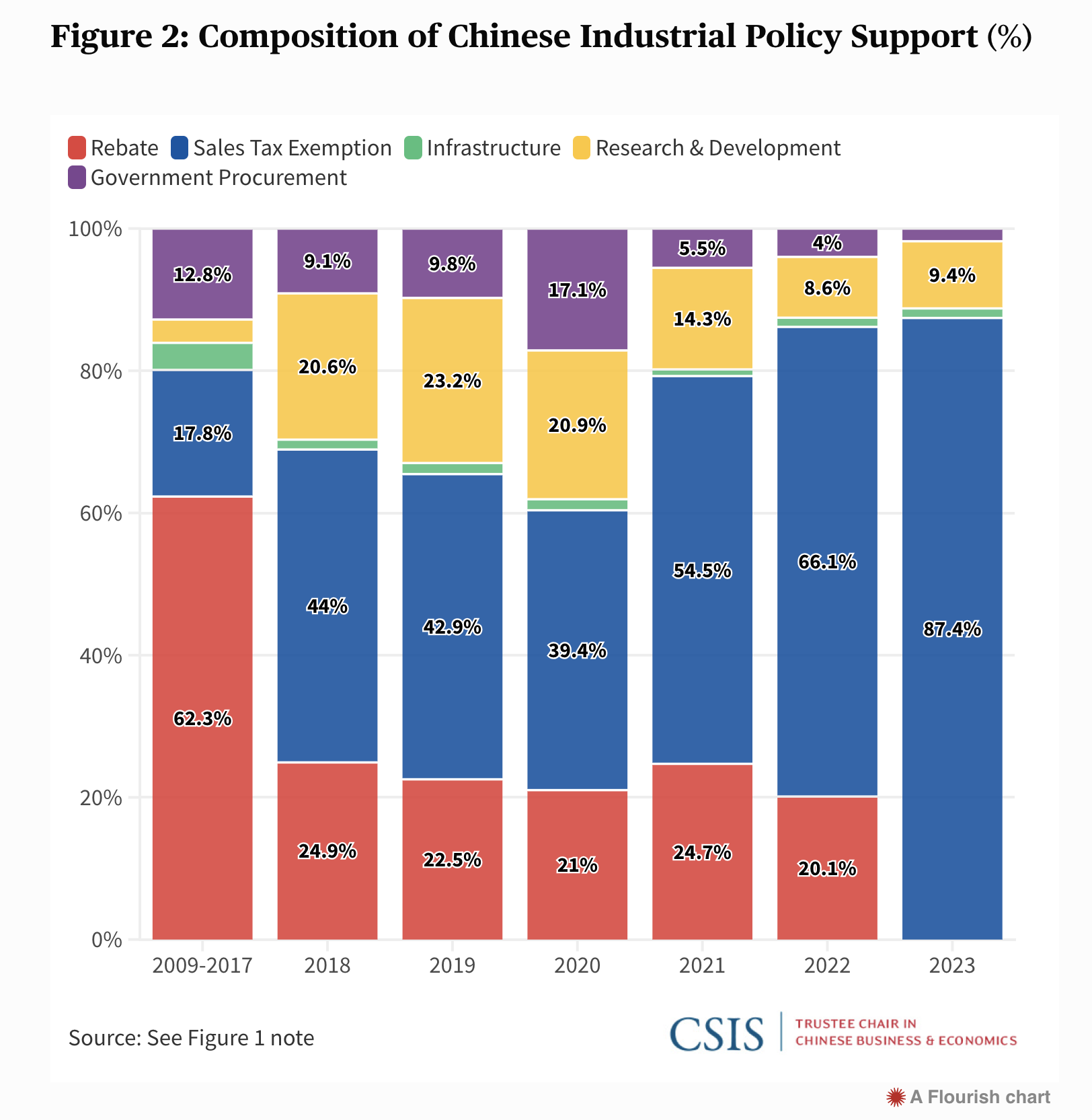

These estimates reflect the combination of five kinds of support: nationally approved buyer rebates, exemption from the 10% sales tax, government funding for infrastructure (primarily charging poles), R&D programs for EV makers, and government procurement of EVs. The buyer’s rebate and sales tax exemption have accounted for the vast majority of support for the industry (see Figure 2). That said, because of the high cost and desire to winnow the field of producers, the central government reduced the buyer’s rebate in 2022 and eliminated it beginning in 2023.

The report from CSIS goes on to elaborate in some detail. “In our view, these data constitute a highly conservative estimate, as they do not include three other kinds of support.” Going on:

First, despite the change in national policy, some localities — including Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Changping District in Beijing — have created modest rebate programs, mainly to encourage ICE owners to switch to EVs. Because it is difficult to obtain a full picture of this support across regions and over the years and these appear to be relatively small programs, this is left out of our estimates.

Second, low cost land, electricity, and credit are not included, primarily because it is extremely difficult to calculate their overall value with any precision. But we know this kind of support is significant and could be critical for some individual EV makers. A recent World Bank report (p. 39) indicates that in 2022 the auto sector as a whole received loans with interest rates of roughly 2%, half the weighted average for all commercial and industrial loans. Some private EV makers have also accepted equity financing from state entities. The most prominent example is NIO, which in 2020 received an RMB 5 billion injection from the Hefei municipal government in exchange for a 17% stake in the company’s core business. Hefei later cashed out most of its holdings in 2022.

Finally, our estimate does not include subsidies for other parts of the supply chain, including for miners and processors of raw materials, chemicals producers, and battery manufacturers. According to the annual reports of CATL, which in 2023 held a 43.1% share of the Chinese market and 36.8% of the global market, its government subsidies have risen from $76.7 million in 2018 to $809.2 million in 2023. EVE Energy, which ranks 4th in China, pulled in $208.9 million in subsidies in 2023. These additional kinds of funding are cumulatively substantial, with low cost credit and equity investment likely being the most impactful for EV makers. Growing subsidies to battery makers may mean an overall shift to greater relative support for them.

There are at least two different ways to interpret the data on industrial policy support for EV makers. China’s trading partners could point to 15 years of sustained regulatory and financial support for domestic producers, which has fundamentally altered the playing field to make it much harder for others to compete in China or anywhere else where Chinese EVs are sold.

By contrast, defenders of China could point out that the data show that subsidies as a percentage of total sales have declined substantially, from over 40% in the early years to only 11.5% in 2023, which reflects a pattern in line with heavier support for infant industries, then a gradual reduction as they mature. In addition, they could note that the average support per vehicle has fallen from $13,860 in 2018 to just under $4,600 in 2023, which is less than the $7,500 credit that goes to buyers of qualifying vehicles as part of the U.S.’s Inflation Reduction Act.

EU Tariffs Proposal Is Not Punitive

Robert Habeck insisted in his remarks in China last week that the proposed tariffs on Chinese-made electric cars are not punitive. Whether Chinese officials believe that or not is an open question. Countries such as the US, Brazil, and Turkey have used punitive tariffs, but not the EU, he said. “Europe does things differently.” He pointed out that the European Commission had spent nine months exploring in detail whether Chinese companies had benefited unfairly from subsidies and that any measures the EU has proposed were meant to compensate for the advantages granted to Chinese companies by Beijing.

Zheng Shanjie, chairman of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, responded: “We will do everything to protect Chinese companies.” The proposed EU tariffs would hurt both sides, he added, and told Habeck he hoped Germany would demonstrate leadership within the EU and “do the correct thing.” He also denied accusations of unfair subsidies, saying the development of China’s new energy industry was the result of comprehensive advantages in technology, market, and industry supply chains, fostered in fierce competition. The growth of China’s electric car industry “is the result of competition, rather than subsidies, let alone unfair competition,” Zheng said.

The Takeaway

For years, we have heard about enormous subsidies for the electric car industry by China. Now, thanks to CSIS, we have some data that backs up that claim. That is not to say that the numbers CSIS published are definitive; we all know numbers can be adjusted to support a variety of claims. Yet they provide a much more detailed starting point for a discussion about Chinese subsidies than most of us have had access to previously. Some will look at those numbers and see a sinister plot by China to dominate world markets as part of a desire to become a dominant player on the world stage. Most Americans are blissfully unaware that many people in the rest of the world see the US as pursuing a similar goal over the past 80 years.

Scott Kennedy, the author or the CSIS report, has some perspectives on that issue that CleanTechnica readers may find instructive. He writes, “Despite the extensive government support and expansion of sales, very few Chinese EV producers and battery makers are profitable. In a well functioning market economy, firms would more carefully gauge their investment in new capacity, and the emergence of such a sharp gap between supply and demand would likely result in industry consolidation, with some mergers and acquisitions, and other poorly performing companies leaving the market entirely.

“In this context, given Chinese EV makers’ scale and reach, it is difficult for other countries’ producers who face tighter budget constraints to effectively compete. My guess, though, is that the endurance of these subsidies is unlikely part of an intentional plot for global domination of this industry and instead a byproduct of China’s inefficient industrial policy system in which support typically extends too long and is spread overly widely, a pathology visible in both tradable and non-tradable industries.”

In other words, be careful what you wish for, China. You just might get it.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.