Lithium Mining In Argentina — Jobs vs. Environment

According to Wikipedia, at 20 mg of lithium per kg of Earth’s crust, lithium is the 25th most abundant element. The Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium says, “Lithium is a comparatively rare element, although it is found in many rocks and some brines, but always in very low concentrations. There are a fairly large number of both lithium mineral and brine deposits but only comparatively few of them are of actual or potential commercial value. Many are very small, others are too low in grade.” One of the places lithium is found in commercially significant concentrations is in the Salinas Grandes, the largest salt flat in Argentina. It is a biodiverse ecosystem known as the Lithium Triangle that is 200 miles long and is located partly in Argentina and partly in Chile and Bolivia.

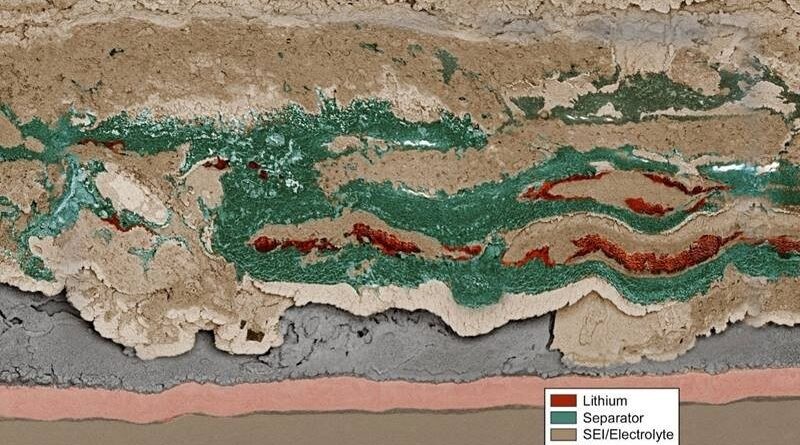

The Harvard International Review says the Lithium Triangle is one of the driest places on earth, which complicates the process of lithium extraction. Miners have to drill holes in the salt flats to pump salty, mineral-rich brine to the surface. They then let the water evaporate for months at a time, forming a mixture of potassium, manganese, borax, and lithium salts that is then filtered and left to evaporate once more. After 12 to 18 months, the filtering process is complete and lithium carbonate can be extracted. While lithium extraction is relatively cheap and effective, it begs the question of sustainability and long-term impact. The question, HIR says, is whether lithium mining will benefit the globe and its inhabitants or lead to societal and environmental harm?

Mineral extraction often takes a toll on Indigenous people. The Harvard report says in Argentina, lithium stockpiles worth billions of dollars lie beneath the ancestral land of the indigenous Atacamas people who have lived in the Salinas Grandes for many generations. Those lithium deposits have attracted the attention of mining companies for years. One of them, a joint Canadian–Chilean venture called Minera Exar, has made an agreement with six Indigenous communities to extract $250 million a year worth of lithium to power cell phones, electric cars, and energy storage batteries. Minera Exar, which is controlled by a Chinese corporation, claimed that each community would receive an annual payment ranging from US$9,000 to US$60,000, but Luisa Jorge, a resident and local leader, said “lithium companies are taking millions of dollars from our lands. They ought to give something back, but they’re not.”

Banding Together To Oppose Lithium Extraction

For years, the 33 Indigenous communities in the Salinas Grandes have banded together to halt mining operations, fearing that their water resources will be lost or contaminated and they will be forced from their land. “Respect our territory” and “No to lithium” signs are seen everywhere on road signs, abandoned buildings, and murals. A report by The Guardian says more than 30 global mining conglomerates are operating in the region, encouraged by the “anarcho-capitalist” Argentinian president Javier Milei. Communities are increasingly divided by offers of work and investment. One has already broken the pact; more are expected to follow.

Water is the primary concern of the Indigenous people. Each ton of lithium requires the evaporation of about 2 million liters (238,000 gallons) of water, which threatens to drain the region’s wetlands and already parched rivers and lakes. It also risks contaminating the groundwater, endangering livestock and small scale agriculture. Clemente Flores, a community leader, says water is the most essential part of “Pachamama” — Mother Earth. “The water feeds the air, the soil, the pastures for the animals, the food we eat,” he argues. “Our message to people with electric cars is that it is not right to ruin a region and destroy communities for a thing you want to buy.”

Flavia Lamas, who serves as a tour guide for visitors to the the salt flats, remembers when a lithium company began exploring the area in 2010. “They told us lithium extraction would not affect our Mother Earth, but then they hit the water. They began draining the salt flat — our land began to degrade in just one month.”

Pía Marchegiani, director of environmental policy at the local Environment and Natural Resources Foundation, told The Guardian that environmental assessments leave gaps in understanding the overall impact of large-scale exploitation. “This area is a watershed. Water will drain from all over, but nobody is looking at the bigger picture. We have the Australians, the US, Europeans, the Chinese, the Koreans. But nobody is adding up all the water use.”

Many Indigenous people have spent centuries on this land, which they consider sacred, ancestral territory. They worry they will be forced to migrate. “We cannot sacrifice the territory of the communities. Do you think it is going to save the planet? On the contrary, we’re destroying Mother Earth herself,” says Flores. Lamas says the mining companies have flocked to the region like the Conquistadors of the 1500s. “The Spaniards brought gifts of mirrors. Now the miners come with trucks. We have been offered gifts, trucks, and houses in the city, but we do not want to live there.”

Marchegiani accuses companies of deploying “divide and rule” tactics. Alicia Chalabe, the lawyer for the Indigenous people of the Salinas Grandes, says the communities face a “permanent pressure” to agree to demands. “It is raining with lithium companies here. There has been a huge increase in the last five years,” she says. “Communities are just the obstacles.”

The Promise Of A Lithium Economy

Mariano Cayata told The Guardian he supports lithium mining and hopes the companies will fix services neglected by the government. “We have asked the government for help with work and better conditions many times for 30 years, but they do not care. We have no faith in them,” he says. “The mines can provide what the government does not. They [the mining companies] said they would improve our water and our roads. And they will because they will need them too.”

Some villagers support the economic growth brought about by the mines. On the road to Olaroz, the town of Susques has expanded rapidly due to mining. It has a modern secondary school, a pharmacy, two petrol stations, and a hotel. Dozens of houses are under construction. A hotel manager, Luis Ortega, says lithium has had a positive economic effect. “A laborer there makes more money than people in the city. It’s had a good impact on the community’s growth. There are better homes and shops,” he says.

While mining projects are already operational, such as those in Olaroz and Hombre Muerto, Argentina’s lithium expansion has just begun. Officials see lithium mining — and the taxes they can collect — as key to lifting the country from its economic crisis as it battles inflation, which peaked at 276.4% in April. Mining companies, meanwhile, are encouraged by the country’s “free market” stance, lax regulation, and low taxes. Recently, President Milei announced he would cut further costs for mining companies to bring in foreign currency.

However, some residents and campaigners accuse the provincial government of abusing human rights in favor of commercial interests. In theory, Indigenous peoples have the right to “prior, free and informed consultation,” which guarantees access to information, participation, and dialogue with the State. A year ago, the regional government made sweeping changes to its constitution, limiting the right to demonstrate and modifying the right to Indigenous lands with the undeclared aim of facilitating lithium mining. Protests erupted, and activists told The Guardian they had been violently repressed.

“We’re not against lithium; we’re against breaching human rights, the criminalization of conflict, the constant human rights violations, the lack of rule of law, the lack of justice,” says Marchegiani. “Researchers estimate 54% of [energy transition] minerals are in or near Indigenous lands. So what kind of energy transition are we looking at here? One that is going to be imposed on vulnerable people?”

In the face of the sector’s economic boom and political repression, many believe that more lithium organisations will begin operating in the next year and that their voices will not be heard. “We are losing the fight,” says Chalabe. Flores asks the international community to consider its priorities. “Lithium is like a needle to extract the blood of our mother — and our mother will die. In 50 years, there will be nothing here.”

The Takeaway

The age-old fight over resources continues. References to the Spanish Conquistadors are a pointed reminder of how the lust for profits can distort local economies. Many nations have seen their land and rights trampled by companies extracting oil and gas from beneath their lands. Lithium is just another version of how extractive industries leave a trail of unintended consequences in their wake. To what extent should social justice be part of the economic system that profits from extracting raw materials? To what extent should environmental considerations take priority over profits?

In the US, the oil and gas industries have devastated many communities that abut the Gulf of Mexico, but legislators and governors in those states want more, because the taxes those companies pay prop up much of those governments. They are on a treadmill and don’t know how to make it stop, so they keep pushing for more oil, more gas, more LNG even as the seas rise around them and more powerful storms pummel their communities.

Americans have also seen their rights to protest obliterated by compliant politicians who will do anything Big Oil, Big Ag, Big Corn, Big Plastic, or any other industry that is generous with its campaign donations asks for. The corrosive effect of profits is everywhere. What is happening in Salinas Grandes is happening in almost every nation on Earth, as commerce and profits enjoy a higher priority than individual liberty and a sustainable environment. The Argentinian people in the Salinas Grandes represent all of humanity. As Walt Kelly told us decades ago, “We have met the enemy and they are us.”

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Videos

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.